Your basket is empty

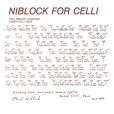

Coming after Nothin To Look At Just A Record, with its densely layered trombones, this is Niblock’s second, rarest LP, from 1984: a collaboration with Joseph Celli (who himself had worked with Cage, Oliveros and Ornette), playing oboe and English horn.

Niblock creates seamless, ringing drones by skilfully cutting all Celli’s breaths and pauses. Play it loud, he says, for its viscerality, and to get its ringing overtones rolling around your room.

‘Renowned for his work on iconic Spaghetti Western scores with Ennio Morricone, and his groundbreaking contributions to library music, Alessandroni lavishes his other-worldly genius on this wonderful cocktail of an album, blending jazz, bossa and lounge, garnished with his signature wordless vocal arrangements and lush instrumentation. Featuring his remarkable talent on guitar, piano, and mandolincello, this album paints a vibrant portrait of 1970s cosmopolitan cool.’

‘Arguably the rarest LP of European free jazz, recorded in 1963 for the Danish label Sonet, but not fully released. Impossibly uncommon, exceptionally wonderful music, featuring an extended tenor saxophone solo by Frits Krogh, influenced by Sonny Rollins, but strikingly his own man. The rhythm section is deep into non-metrical time, and comparisons to Cecil Taylor are valid, though Prehn’s playing favours chords and clusters over linear runs. For the CD, the two tracks of the original LP, mastered from both extant copies of the test master, are augmented by a single track from 1966, never before released.’

Legendary free jazz recordings from 1964 and 1965, with the Danish pianist alongside Fritz Krogh on tenor saxophone, Poul Ehlers on bass, and Finn Slumstrup on drums.

‘Close-miked percussive sax-pad treatments that swing like mad and give the music a VERY radical profile and color,’ writes Mats Gustafsson in his liner notes. ‘I have NEVER heard anything like it.’

Ten vivid, dynamic dubs from Randy’s legendary Studio 17, in North Parade, with Karl Pitterson taking over from Errol Thompson, alongside Clive Chin… stripping, tweaking and burnishing these superbly limber rhythms by Skin Flesh & Bones, the Wailers Band and Now Generation.

Pure, expert instrumental reggae — no bells, no whistles — to run alongside vocal cuts by Ta-Teasha Love, Tony Tuff, Carlos Malcolm and co.

Originally released on Impact! in 1975, in a pressing of barely two hundred copies.

The brilliant trumpeter’s final album as leader, from 2007 — fresh, nimble, exuberant, reaching, with Billy Bang on violin and Bryan Carrott on vibraharp.

Ace Brazilian funk from 1977, with a flagrant dose of the Herbies.

D.K. and Low Jack.

Characteristically brilliant ebullience from the Art Ensemble trumpeter in 1974, with John Hicks (doing Hello Dolly as a duet), John Stubblefield, bro Joseph Bowie from Defunkt, Julius Hemphill (on Ornette’s Lonely Woman), Bob Stewart, Cecil McBee, Jerome Cooper, Charles Shaw and Phillip Wilson.

‘High energy beats from the kings of Bamako’s sound-system street-party scene, as featured on the Balani Show compilation. Cut-up samples of baliphones, djembes and talking drums, spliced together into heavy studio tracks. Future bass sounds — a Malian mix of kuduro, decale, dancehall, and trap.’

Scarce.

‘Psychedelic funk, cosmic disco, Balearica… and beyond!’