Your basket is empty

DJ Ramon Sucesso

Sexta dos Crias 2.0

Lugar Alto

Mental baile future-funk.

Impossibly, round two ratchets through higher gears than before. The cutting and scratching skills are brutally imperious, by turn eviscerating in split seconds a trembling flock of far-flung musical prey. Out of the wreckage looms a kind of apocalyptic Techno Scratch terror; the vengeful prophesy of forebears like Grand Wizzard Theodore and the Knights of the Turntable.

Hot, hot, hot.

Impatiently returning to the golden age of Ecuadorian musica national, this second round of retrievals is more of a selectors’ affair: less reverent, more free-flowing, with more twists and turns. There is no let-up in the quality of the music, maintaining the same judicious, heart-piercing balance between emotional desolation and dignified endurance, the same bitter-sweet play between affective excess and formal sublimity.

This time around, the woman steal the show. Laura and Mercedes Suasti were child stars, with an exclusive Radio Quito contract. Unlike nearly all the men here, they lived long and prospered: Mercedes died last year, at the age of 93. Gladys Viera and Olga Gutierrez both came to Ecuador from Argentina. To start, Gladys plugged the scandalous new Monokini swimwear; Olga performed for visiting British royalty in 1962. Olga was glamorous but tough. She would make little of the amputation of one of her legs: ‘I don’t sing with my leg.’ She is accompanied on our opener by quintessentially reeling, sultry musica national: haunted-house organ, twinkling xylophone, Guillermo Rodriguez’ heart-plucking guitar-playing, and lilting, dance-to-keep-from-crying double-bass. ‘Sometimes I think that you will leave me with no memories,’ she sings, ‘that you hold only disappointments in store for me… In the future your love will search me out, full of regret. By then it will be too late, there will be no consolation, only disappointment awaiting you.’

Other highlights include the two contributions of Orquesta Nacional: Ponchito Al Hombro, like an off-the-wall forerunner of the Love Unlimited Orchestra, beamed into the tropics from an unknowable time and space; and the tone poem Atahualpa, a mystical yumbo invoking Quito’s most ancient inhabitants, the Kichwa. Also the tremulous, gypsy-flavoured violin-playing of Raul Emiliani, who arrived in Quito from Italy, suffering PTSD from the Second World War; the inscrutable, sardonic experimentalism of organist Lucho Munoz; and the mooing and whistling of Toro Barroso — cow-thief school of Lee Perry — in which a muddy bull dashes home to his darling chola, fearless, full of desire.

Lavishly presented, with a full-size, full-colour booklet, with transporting art-work and expert notes. Luminous sound, by way of Abbey Road, D&M and Pallas.

Truly spell-binding music.

‘The sacred music of peasants in Chile’s remote Central Valley: a communal form of worship and reflection, played in packed rooms throughout the night when work is done. The Canto has persisted for centuries in the voices of hundreds of men and women who conjure vivid visions of apocalypse, the divine, and angelitos (very young children who have died). But the verses are also rooted in the daily life in the valley — labour and drought, family, animals, and the life cycles of plants. To hypnotic accompaniment by guitar and the celestial, 25-string guitarron, countless entonaciones or melodies range across the 10-line rhyming decimas, in an ancient song form originating in Spain and found from South America to the Mississippi Delta. The combination is entrancing and transporting, cosmic and earthly at once.

‘The handsome gatefold jacket presents the visionary, apocalyptic art of Frederico Lohse, a baker from the village of Los Vilos, who painted on old flour sacks; with an eight-page booklet containing lyrics, photos, and extensive notes about the Canto tradition.’

Originally released in 1979 — ‘a product of my hybrid musical influences that joins together flavours of marchinhas de carnaval, frevo, toada, classical, baião, mpb and jazz,’ says Antonio.

The opener Cascavel is a gold-plated London jazz-dance classic; and the last-ever record spun at Plastic People.

The first-ever vinyl reissue of this ravishingly beautiful private press album from 1988; Agustín’s most sought-after LP.

‘By now, Agustín had established himself as one of Argentina’s foremost interpreters of Brazilian music. The seventies brought success with his group Candeias, and recognition in Brazil, where he formed friendships and collaborations with luminaries such as Vinicius de Moraes, Baden Powell, Dorival Caymmi, Toquinho, and Maria Bethania. Following the era of dictatorship in South America, Agustín spent the late seventies and early eighties living and touring in Norway, during European travels with his quartet.

‘Recorded after returning to his native Buenos Aires — and featuring a team of crack Argentinian musicians, including drummer Osvaldo Avena, flautist Rubén Izarrualde, and saxophonist Bernardo Baraj — Puertos de Alternativa emerged from this confluence of diverse experiences, contexts, and influences. It begins rooted deeply in South American soil, drawing clear inspiration from Brazilian guitar masters like Heitor Villa Lobos, Garoto, and Baden Powell. But a sense of journey unfolds, evoking new landscapes and horizons — from the crystalline beauty of glacial Norway to the gentle currents of the Rio de la Plata.’

Ary was the most celebrated of those singers and songwriters emerging from Belem do Para in the 1950s, with deep Afro-Brazilian roots. He kick-started the sixties with his best LP Aqui Mora O Ritmo, The Rhythm Is Here. One year later his album Cheguei Na Lua (I Landed On The Moon) revealed his passion for space travelling and for the moon in particular. He released one LP per year till he left RCA in 1966. He made a ton of money and lived notoriously large.

The sleeve-notes of his 1958 debut Forro Con Ary Lobo are quick to nail his accomplishment: ‘An absolute master of Baiao, Coco, Batuque and other related musical genres, and the owner of an art one hundred percent his own, Ary Lobo is the ideal

interpreter of northeastern songs.’

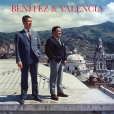

Gonzalo Benitez and Luis Alberto Valencia were kingpins of the musica nacional movement in Ecuador. Check them out on the cover, on a rooftop in Quito’s Old Town, surveying their dominion.

In 1970, when Valencia collapsed onstage during a performance of the yaravi Desesperacion — ‘My heart is already in ashes’ — and died four days later, aged 52, his coffin was carried through those city streets on the shoulders of a throng of his fans.

They began singing as a duo in their mid-teens. During twenty-eight years together they recorded more than six hundred songs, for Discos Ecuador, Nacional, Granja, Ortiz, Rondador, Onix, Fuente, Real, Tropical, Fadisa, RCA Victor — and of course CAIFE.

Their exquisitely romantic harmonising is a sublime blend of collected forbearance and abject self-annihilation, underpinned and elaborated by the heart-piercing, improvisatory guitar-playing of Bolivar Ortiz. Effectively the third member of the group. ‘El Pollo’ sets the tone and intensity for everything that follows: listen to his soloing at the start of our opener, Lamparilla.

Musically a pasillo — a cross between a Viennese waltz and the indigenous yaravi rhythm — Lamparilla draws its verses from a poem by Luz Martinez from Riobamba, written in 1918 when she was 15, under the influence of Baudelaire and Mallarme. Another pasillo here, Sombras (‘Shadows’) is one of the best-loved songs in the musica nacional canon, setting poetry about undercover sex and lost love by the Mexican poet Maria Pren, which was considered pornographic on publication in 1911. ‘When oblivion comes / I will lose you to the shadows / To the hazy gloom / Where one warm afternoon I laid bare my unbridled feelings for you / Never again will I search out your eyes / Or kiss your mouth.’

And Benitez & Valencia looked back still further, to the indigenous roots of Ecuadorian music, as the key to its future. Carnaval de Guaranda is their take on a song dating back to the era of the Mitimaes, a broad group of Bolivian tribes conquered by the Incas and displaced to Ecuador. ‘Impossible love of mine / I love you for being impossible / Who loves what is impossible / Is the truest lover.’

Fiercely beautiful, desolate music from the shadowy mists of time, the lip of oblivion, for anyone who had a heart, for anyone who ever dreamed.

The Psych Funk 101 selectors smashing it over again with this lovingly annotated selection of 45s.

‘Starry-eyed Brazilian love songs, ambient vignettes, warm, home-cooked beats and gentle strokes of MPB genius.’ Even a shot of West African high life!

‘The beautifully laid back sunshine soul opener has all the charm of early-70s João Donato… On the R&B inspired Quero Dizer, the swirling, lo-fi, kalimba and guitar-fronted beat is turned into a feel-good hit by the ingenuity of Berle’s honey-soaked vocal melody… Powerfully intimate, O Nome Do Meu Amor is a guaranteed tearjerker, with his stunning voice soaring over gently plucked acoustic guitar and the textural flutter of soft movement, as if we hear him writing the song in the moment…’

“A super, subtle, beautiful record,” says Gilles Peterson.

Astounding, deeply exploratory, previously unreleased work by the legendary Brazilian percussionist and composer.

A wild and unsettling collage, implacably original and startlingly intense — from the electroacoustic opener, which channels ancestral African inspirations into cosmogony, through the proto-mixtape Exemplo de Sintetizadores, which transitions from transcendental drones to astral cha-cha-chas, to a musical consideration of dripping water, in Suite Contagotas.

Djalma is best known for his studio work on benchmark albums, including numerous classics by Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, and Jorge Ben, and for his own polyrhythmic opus Baiafro; and the finale here was first performed at the 1964 Nós, Por Exemplo concert, an event often cited as the inauguration of the Tropicalia movement. Djalma brings the electronics — medical oscillators, for example — to beef up his percussion. It’s eye-opening.

Corrêa called it ‘spontaneous music’; sonic adventures ranging audaciously across an array of genres, from jazz to deep funk to complete abstraction, all imbued with his signature DIY ethic.

Drawn from the original master-tapes, guided by Corrêa himself, just prior to his death.

Intriguing, immersive music. Dazzling, engrossing artwork, too.

Classic Brazilian boogie, from 1983; including a killer version of Tania Maria’s Come With Me — Vem Menina — and the dancefloor smash O Amigo De Nova York.

Her classic third LP, from 1971, originally released by Odeon Brazil.

‘Gems like Que Bandeira, composed by Marcos Valle, blending funk/soul and bossa/MPB; Esperar Prá Ver, co-written by her brother Renato Corrêa, with its stunning arrangement and an epic bassline that is hard to get out of your head; the archetypal samba soul of Só Quero; and vocal-driven groovy jams like Por Mera Coincidência and Rico Sem Dinheiro, spiced with celestial strings and heavy-duty drums and basslines.’