Your basket is empty

Peter Brotzmann (sax), Toshinori Kondo (trumpet), Frank Wright (sax), Willem Breuker (sax), Hannes Bauer (sax), Alan Tomlinson (trombone), Alexander Von Schlippenbach (piano), Harry Miller (bass), Louis Moholo (drums).

LP from Cien Fuegos.

Monumental free jazz, still blinding.

With Willem Breuker and Evan Parker also on saxophones, Fred Van Hove on piano, Peter Kowald and Buschi Niebergall on double basses, Han Bennink and Sven-Ake Johansson both playing drums.

The CD is on FMP, with two extra takes.

Our favourite of all his records.

From 1984, inspired by a Kenneth Patchen chapbook, it favours tenderness, lyricism and expressivity, but without foregoing Brötzmann’s characteristic squalling ferocity and angst. It never drags: he plays baritone, tenor and alto saxes, different clarinets including bass clarinet, and tarogato, bringing every trick and technique to bear on a whirl of feelings and emotions, in pieces nearly all less than five minutes. Bar the gorgeous opening reading of Lonely Woman, it’s all improvised, but utterly compelling, reflective, melodious, ravishing and rawly personal.

Beautiful music; hotly recommended.

E-flat, b-flat and bass clarinets, soprano and alto saxophones, birdcalls, viola, banjo, cymbals, wood, trees, sand, land, water, air.

Recorded outdoors in 1977, in the Black Forest, near Aufen.

Saxophone, clarinet, tarogato, frame drum, vocals.

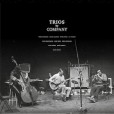

A typically eclectic collection of guests joined Derek Bailey for Company Week in 1983: saxophonists Evan Parker and Peter Brötzmann; cellist Ernst Reijseger, mainstay of Dutch new jazz (ICP Orchestra, Clusone Trio); American wind virtuoso J.D.Parran, veteran of the Black Artists’ Group and Anthony Davis and Anthony Braxton ensembles.

The French bassist Joëlle Léandre is equally at home playing free or performing works by Cage and Scelsi, while Vinko Globokar is an acclaimed composer as well as a trombonist of monstrous virtuosity.

British electronics pioneer Hugh Davies served time alongside Globokar with Karlheinz Stockhausen. Percussionist Jamie Muir was with Davies on the very first (Music Improvisation) Company outing in 1970, before a brief stint with King Crimson.

Is there an ideal number of musicians for free improvisation? Bailey once described playing solo as a “second-rate activity” – though he did it spectacularly well – while at the other end of the spectrum, large improvising ensembles can descend into an unwieldy racket.

Three may be a crowd for some, but for Pythagoras it was the perfect number, and trios work surprisingly well in improvised music. Sometimes one instrument takes centre stage, like Parker’s circular-breathing soprano at the beginning of Five, but knowing when to lie low, as he does in the brief austere Three, is just as crucial to the success of the whole. Muir makes sure he doesn’t get in the way of Globokar and Parran’s leisurely exchanges on Four, but the trombonist is all over the place on One, with Léandre racing up and down her bass and Davies all spikes, squeaks and squiggles.

With a touch of Bailey’s dry humour, two of these seven recordings aren’t trios at all: Trio Minus One is his duo with Reijseger, running the gamut from crazed polyrhythmic strumming (imagine Reinhardt and Grappelli playing Schoenberg and Nancarrow simultaneously) to what must be the fastest cello pizzicati ever recorded. And on the closing ecstatic nonet, Brötzmann and trumpeter John Corbett prove that more cooks don’t necessarily spoil the broth but sure as hell can spice it up.

‘Brotzmann barely plays saxophone at all, sticking mostly to tarogato and a host of clarinets; Nilssen-Love mostly plays gongs, bells and other metal percussion. With the changes in tools comes a change in approach. Nilssen-Love is sparer and more decorative, providing accentuating commentary that highlights the more solemn and yearning aspects of his partner’s playing, and Brotzmann explores melancholy to devastating effect. This is a career peak for the recently departed reedist’ (Bill Meyer, The Wire).