Your basket is empty

Moritz from Basic Channel and Rhythm And Sound, alongside Vladislav Delay (Chain Reaction) and Max Loderbauer (Sahko): a dream crossing of classic Berlin techno, On-The-Corner Miles, Larry Heard, and Can.

A stunning survey of the 1970s heyday of this great Japanese singer and countercultural icon.

Deep-indigo, dead-of-night enka, folk and blues, inhaling Billie Holiday and Nina Simone down to the bone.

A traditional waltz abuts Nico-style incantation; defamiliarised versions of Oscar Brown Jr and Bessie Smith collide with big-band experiments alongside Shuji Terayama; a sitar-led psychedelic wig-out runs into a killer excursion in modal, spiritual jazz.

Existentialism and noir, mystery and allure, hurt and hauteur.

With excellent notes by Alan Cummings and the fabulous photographs of Hitoshi Jin Tamura.

Hotly recommended.

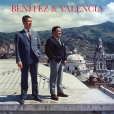

Gonzalo Benitez and Luis Alberto Valencia were kingpins of the musica nacional movement in Ecuador. Check them out on the cover, on a rooftop in Quito’s Old Town, surveying their dominion.

In 1970, when Valencia collapsed onstage during a performance of the yaravi Desesperacion — ‘My heart is already in ashes’ — and died four days later, aged 52, his coffin was carried through those city streets on the shoulders of a throng of his fans.

They began singing as a duo in their mid-teens. During twenty-eight years together they recorded more than six hundred songs, for Discos Ecuador, Nacional, Granja, Ortiz, Rondador, Onix, Fuente, Real, Tropical, Fadisa, RCA Victor — and of course CAIFE.

Their exquisitely romantic harmonising is a sublime blend of collected forbearance and abject self-annihilation, underpinned and elaborated by the heart-piercing, improvisatory guitar-playing of Bolivar Ortiz. Effectively the third member of the group. ‘El Pollo’ sets the tone and intensity for everything that follows: listen to his soloing at the start of our opener, Lamparilla.

Musically a pasillo — a cross between a Viennese waltz and the indigenous yaravi rhythm — Lamparilla draws its verses from a poem by Luz Martinez from Riobamba, written in 1918 when she was 15, under the influence of Baudelaire and Mallarme. Another pasillo here, Sombras (‘Shadows’) is one of the best-loved songs in the musica nacional canon, setting poetry about undercover sex and lost love by the Mexican poet Maria Pren, which was considered pornographic on publication in 1911. ‘When oblivion comes / I will lose you to the shadows / To the hazy gloom / Where one warm afternoon I laid bare my unbridled feelings for you / Never again will I search out your eyes / Or kiss your mouth.’

And Benitez & Valencia looked back still further, to the indigenous roots of Ecuadorian music, as the key to its future. Carnaval de Guaranda is their take on a song dating back to the era of the Mitimaes, a broad group of Bolivian tribes conquered by the Incas and displaced to Ecuador. ‘Impossible love of mine / I love you for being impossible / Who loves what is impossible / Is the truest lover.’

Fiercely beautiful, desolate music from the shadowy mists of time, the lip of oblivion, for anyone who had a heart, for anyone who ever dreamed.

Headlong, fierce, banked rasta drumming fit to discombobulate any kind of system, with sweet, jazzy trombone riding it down, bubbling bass driving it home, and all of it classically dubwise.

Wareika Hill Sounds is the contemporary roots reggae project of Calvin Cameron — mainstay of the original Light Of Saba line-up, the genius behind Lambs Bread Collie — who to this day lives above the headquarters of the Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari, in the Wareika Hill district of Kingston, Jamaica.

In the great pedagogical traditions of the multi-cultural Light Of Saba, and before that Count Ossie, this new recording runs together two JA musical traditions — a kind of drumming (and drum) brought from the Congo, and the island’s variation of calypso — into a thundering grounation charge. As always, the Skatalite’s trombone-playing is majestic: deadly, gripping, deeply cultivated.

The dub is tremendous, too.

‘From the college where you get your musical knowledge, shower on the hour every hour’ — as I-Roy would say, in a Leninist style and fashion — ‘Knowledge Is Power.’

With our logo on the front of the shirt, as shown to the far left; and blown up, centred, on the back.

Impatiently returning to the golden age of Ecuadorian musica national, this second round of retrievals is more of a selectors’ affair: less reverent, more free-flowing, with more twists and turns. There is no let-up in the quality of the music, maintaining the same judicious, heart-piercing balance between emotional desolation and dignified endurance, the same bitter-sweet play between affective excess and formal sublimity.

This time around, the woman steal the show. Laura and Mercedes Suasti were child stars, with an exclusive Radio Quito contract. Unlike nearly all the men here, they lived long and prospered: Mercedes died last year, at the age of 93. Gladys Viera and Olga Gutierrez both came to Ecuador from Argentina. To start, Gladys plugged the scandalous new Monokini swimwear; Olga performed for visiting British royalty in 1962. Olga was glamorous but tough. She would make little of the amputation of one of her legs: ‘I don’t sing with my leg.’ She is accompanied on our opener by quintessentially reeling, sultry musica national: haunted-house organ, twinkling xylophone, Guillermo Rodriguez’ heart-plucking guitar-playing, and lilting, dance-to-keep-from-crying double-bass. ‘Sometimes I think that you will leave me with no memories,’ she sings, ‘that you hold only disappointments in store for me… In the future your love will search me out, full of regret. By then it will be too late, there will be no consolation, only disappointment awaiting you.’

Other highlights include the two contributions of Orquesta Nacional: Ponchito Al Hombro, like an off-the-wall forerunner of the Love Unlimited Orchestra, beamed into the tropics from an unknowable time and space; and the tone poem Atahualpa, a mystical yumbo invoking Quito’s most ancient inhabitants, the Kichwa. Also the tremulous, gypsy-flavoured violin-playing of Raul Emiliani, who arrived in Quito from Italy, suffering PTSD from the Second World War; the inscrutable, sardonic experimentalism of organist Lucho Munoz; and the mooing and whistling of Toro Barroso — cow-thief school of Lee Perry — in which a muddy bull dashes home to his darling chola, fearless, full of desire.

Lavishly presented, with a full-size, full-colour booklet, with transporting art-work and expert notes. Luminous sound, by way of Abbey Road, D&M and Pallas.

Truly spell-binding music.

A dazzling survey of the last, bohemian flowering of the so-called Golden Era of Ecuadorian musica national, before the oil boom and incoming musical styles — especially cumbia — swept away its achingly beautiful, phantasmagorical, utopian juggling of indigenous and mestizo traditions.

Forms like the tonada, albazo, danzante, yaravi, carnaval, and sanjuanito; the yumbo, with roots in pre-Incan ritual, and the pasillo, a take on the Viennese waltz, arriving through the Caribbean via Portugal and Spain.

Exhumations like the astoundingly out-there organist Lucho Munoz, from Panama, toying with the expressive and technical limits of his instrument; and our curtain-raiser Biluka, who travelled to Quito from Rio, naming his new band Los Canibales in honour of the late-twenties Cannibalist movement back home, dedicated to cannibalising other cultures in the fight against post-colonial, Eurocentric hegemony. He played the ficus leaf, hands-free, laying it on his tongue. One leaf was playable for ten hours. He spent long periods living on the street, in rags, when he wasn’t in the CAIFE studio recording his chamber jazz-from-space, with the swing, elegance and detail of Ellington’s small groups, crossed with the brassy energy of ska — try Cashari Shunguito — and an enthralling other-worldliness.

Utterly scintillating guitar-playing, prowling double bass, piercing dulzaina, wailing organ, rollicking gypsy violin, brass, accordion, harps, and flutes. Bangers to get drunk and dance to. Slow songs galore to drown your sorrows in, with wildly sentimental lyrics drawn from the Generacion Decapitada group of poets (who all killed themselves); expert heart-breakers, with the raw passion of the best rembetica, but reined in, like the best fado.

Fabulous music, like nothing else, exquisitely suffused with sadness and soul. Hotly recommended.

Sumptuously presented, in a gatefold sleeve and printed inners, with a full-size, full-colour booklet, with wonderful photos and excellent notes. Limpid sound, too, courtesy of original reels in Quito, and Abbey Road in London; pressed at Pallas.

‘... compelling and eccentric mix of lopsided funk, freaky jazz and African disco, which gets through more rhythms than some people hear in a lifetime’, Time Out ; ‘***** pure bliss’, Kevin ‘The Bug’ Martin, Muzik.

Visceral, elemental, electronic funk, conjured from scraps of sound, breath, mutterings, dubwise remembrances, scuffling, sweat and blood, thin air — ‘crawled out of the slime’, as the opener puts it, self-engendering like the baddie in Terminator — all harnessed to cruelly grooving earthquake bass and b-boy drum science.

Rhythmically it has ants in its pants and it needs to dance, with an improvisatory, streetwise nervous energy and uninhibited, purposeful rapture — akin to this guy, say, eighteen minutes in — crossed with on-song Pepe Bradock and stripped-to-the-bone, mongrel hip-hop.

It’s unruly and edgy, a bit off its rocker, emotionally ranging — typically anxious, often nostalgic — and riveting dance music.

Judge-dread mastering by D&M; first-class Pallas pressing; stunning gatefold artwork by Will Bankhead.

Ruff ruff ruff.

Three brilliant re-routings of Detroit machine funk — Moodymann in particular — into deep mid-Atlantic co-minglings with raw, old-school hiphop and house.

Str8 Crooked is clattering, chugging jack, holding something like Paisley soul under the water; Build Back Better Sweatshops is more driving, riven with breakdowns and horror-show vocal samples. With an uptempo downbeat which nonetheless sounds like a tolling bell, the epic, immersive, sixteen-minutes-plus Episcopi Vagantes pulls off the deadly combination of a kind of stifled, timeworn, melodic wistfulness and percussively restless, passing-through urgency.

This is killer dance music, run through with swingeing, parping bass and ruff b-boy drum-machine rhythms: encrusted and detailed, mangled and nervy, but intensely hard-grooving; wired with punk insouciance, edginess, and free spirit.

Bim bim bim.

Red and pink on dark navy. Premium cotton, smooth and durable. 67cm shoulder strap.

Takes twenty-odd LPs.

White on grey. Premium cotton, smooth and durable. 67cm shoulder strap.

Takes twenty-odd LPs.

Bedazzled nipper with red Honest Jons ball.

With loving detail reproducing the label of the original Lord Kitchener 78, in all its finery. Expertly hand-printed in zinging pinkish red and canary yellow (and white and black), on Gildan ‘ultra cotton’ shirts. Bim.

Bedazzled nipper with orange Honest Jons ball.

The first of three 10” comprising Charlotte Courbe’s third album; her compelling return to Honest Jon’s after two decades, laced with surprise and subversiveness, and a refreshing, unique candour.

After a cancer diagnosis last year, Charlotte felt the urge to produce and release new music. “It became like a vital thing.”

MRI Song and Planet Ping Pong were recorded during chemotherapy. Mind Contorted is a duet with Terry Hall, also featuring Terry’s son Theodore and Noel Gallagher on guitars, in a cover of Daniel Johnston. The song Fourteen Years is the oldest inclusion, announcing a fresh, freer direction.

The sleeve exclusively presents new work by John Stezaker, in the first of a triptych.

“I put out the first Le Volume Courbe single in 2001… she reminded me of a female Syd Barrett… real psychedelic soul” (Alan McGee).

“Inspiring originality, fiercely independent, beautiful music, always years ahead of its time. I remember hearing Charlotte’s music for the first time and being immediately taken by the freshness, great melodies and utterly unique approach” (Kevin Shields).

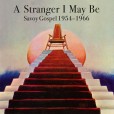

The first of three volumes surveying surely the mightiest Gospel label of them all.

Stomping, rollicking gospel music, intermingling with raw soul, searing blues, hard-rocking doo-wop and jazz, and storming r&b.

Infused and incandescent with the hurting, surging indignation of the Civil Rights movement, here are twenty-four precious scorchers by giants like the Staple Singers and Jimmy Scott, alongside devastating sides by less celebrated names like the Harmonising Five of Burlington, North Carolina, and teen-group the North Philadelphia Juniors, culminating triumphantly with slamming, sanctified versions of Hit The Road Jack and Wade In The Water. Drawn from nigh-impossible-to-find 78s, sevens and LPs, hardly any of these recordings have been reissued since their first release.

Presented in a gatefold sleeve, with full-size booklet; beautifully designed, with stunning, rare photographs and original Savoy artwork. Sound restoration and mastering at Abbey Road; pressed at Pallas.

Co-curated by Greg Belson, compiler of Divine Disco; with deep, extensive notes by Robert Marovich, author of A City Called Heaven: Chicago and the Birth of Gospel Music (University of Illinois), and host of the award-winning radio show Gospel Memories.

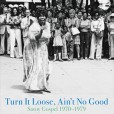

The second of three volumes presents sublime crossings of gospel with the soul, funk and jazz of the Black Power era. Twenty cuts dot dazzlingly between Muscle Shoals soul, screwed breakbeat, Mizells-style fusion, disco and proto-house. Triumphant re-workings of Sly Stone, Donny Hathaway and Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters will have listeners throwing their pew cushions into the air.

Seventeen gems of fierce funk, rapturous soul and transcendent disco and boogie, super-charged with celebration and affirmativeness, loaded with roaring choirs, rocking horns and popping bass guitars, from the years leading up to Savoy’s acquisition by Malaco.

An extensive, sumptuous survey of surely the mightiest Gospel label of them all.

Sixty-one gems of stomping, rollicking, desolate, ravishing gospel music, intermingling with soul, blues, doo-wop, jazz, r&b, disco and boogie.

Presented as a sixty-page mini-book, with CDs suspended in card sleeves; perfect-bound, exorbitantly expensive to produce, lovely.

London Is The Place For Me

7 And 8: Calypso, Palm-Wine, Mento, Joropo, String Band; Kitch In England

Honest Jon's Records

The latest volumes in this much-loved, highly-acclaimed series presenting the music of the Windrush milieu: the post-war, London recordings of West Indians and West Africans, in the first wave of modern migration to Britain.

‘One of the delights of the age’ (Songlines).

’Superlative’ (Mojo); ’superlative’ (Independent); ’sensational’ (Observer).

‘Hugely evocative and poignant’ (Daily Telegraph); ’sheer joy from start to finish’ (Sunday Telegraph); ‘a witty and joyous testament’ (Guardian).

‘Impeccably curated and packaged’ (Wire).

***** Mojo, ***** Times, ***** Independent, ***** Daily Telegraph, ***** Evening Standard, ***** Metro.

Presented as a luxurious mini-book — all paper, no plastic — with suspended card sleeves for the discs. Forty pages of fabulous, previously-unseen photos and full notes, including a terrific, specially-commissioned essay by Kitch biographer Anthony Joseph.

Still deeper forays into the musical landscape of the Windrush generation.

A dazzling range of calypso, mento, joropo, steelband, palm-wine and r’n'b. Expert revivals of stringband music, from way back, alongside proto-Afro-funk.

An uproarious selection of songs about the H-Bomb and modern phones, prostitution and Haile Selassie, mid-life crisis and the London Underground, racism and solidarity, the Highway Code and a 100% West Indian Royal Wedding.

For example some frantic British-Guianan joropo music-hall about Eatwell Brown from Clapham, who starts out biting off a piece of his mother-in-law’s face at a party, then devours everything in his path… a chunk of Brixton Prison, a Union Jack, a policeman’s uniform. Or Marie Bryant — collaborator of Lester Young and Duke Ellington — taking time off from skewering the South African PM Daniel Malan at her West End revue, to contribute some arch, swinging filth about uber-genitalia.

Superior sound, courtesy of Abbey Road, D&M and Pallas; lovely gatefold sleeve; full-size booklet, with full notes, and fabulous previously-unseen photographs, including a set from the family archive of Russ Henderson (who led the first, impromptu Notting Hill Carnival march, in 1966).

The genius of Lord Kitchener has been the mainstay of our series.

In this volume devoted to his post-war London recordings, Kitch plays his many roles with signature aplomb and poised subtlety.

First there is the hooligan chantwell, up for anything in the hurly-burly of carnival proper; and then the casual reporter, firing off postcards to Trinidad about taxis, flashy booze, fast women and football in Manchester, with homesickness and grievance nestled just behind the optimism, pride and tentative senses of belonging.

There is the bearer of news from home, in detailed accounts of murders, tales of stupid local coppers, and reminiscences about food and particular mango trees; the political thinker, considering racism and Africa; and the diarist, with his vivid tales of infidelity, and disclosure of the break-up of his marriage, and his desire to get away.

One foot in the UK, the other in Trinidad; but the man himself somewhere in-between. Kitch In The Jungle, nobody around. A ‘diasporic explorer’; a key twentieth-century witness, alongside such hallowed figures as Samuel Selvon and Edward Kamau Braithwaite.

Though in frustration Kitch would sometimes take over double-bass duties himself, the musicianship of Rupert Nurse, Fitzroy Coleman and co is top-notch. The original glorious sound is down to Denys Preston, recording for Melodisc, often at Abbey Road Studios (where we transferred and restored the 78s compiled here).

Presented in a lovely gatefold sleeve, with a full-size booklet containing superb, specially-commissioned sleevenotes by Kitch biographer Anthony Joseph, and fabulous, previously-unseen photographs.

Derek Bailey’s guests for Company Week at London’s ICA in July 1982 were contemporary classical pianist Ursula Oppens, folk/jazz singer-turned-improviser Julie Tippetts and her partner pianist Keith Tippett, violinist/electronics wizard Philipp Wachsmann, guitarist Fred Frith, trombonist George Lewis, harpist Anne LeBaron, and from Japan free jazz bassist Motoharu Yoshizawa and sound artist Akio Suzuki.

Altogether they performed the stunning extended improvisation Epiphany.

In different, more intimate lineups they detonated numerous Epiphanies.

Here, to start, Yoshizawa and Oppens (both on the keyboard and inside her piano) bounce ideas off each other like ping-pong balls.

Then Tippetts, Wachsmann and Bailey do extraterrestrial cubist flamenco; and Lewis and Frith rumble at everyone magnificently.

Tippett and Oppens kaleidoscope the entire history of the piano into just over fifteen minutes (Fourth and Fifth) with added seasoning from LeBaron and Wachsmann.

To close, Akio Suzuki — despite once describing himself as “pursuing listening as a practice” — makes one hell of a racket with his self-made instruments: a flute, a spring gong and his analapos (two single-lidded cylinders attached by a long steel coil, which he can manipulate and strike, besides vocalising into the tube). Yoshizawa and Bailey give him a real run for his money, and it all builds to an ecstatic, swirling, grinding climax, with Suzuki whooping and hollering wildly.